A few years ago Chris Bye and I were in Louisiana talking about how to use CalmConnect when someone stood up and said, “I have to tell you what happened to me.” She spoke eloquently of the heartache and challenges of working with a small group of severely traumatized elementary students, and the changes she’s seen in the children since using CalmConnect. One six-year-old boy had been exposed to cocaine repeatedly through his mother’s use during pregnancy and had also suffered a gunshot wound to the head. Now he screamed all day long. A young girl was mute, largely catatonic, with significant cognitive and developmental delays. When using CalmConnect, the young boy stops screaming and becomes calm. The young girl hugs the small screen when a sequence ends, and she’s begun to talk quietly in class.

Many years ago, during the 1950’s, American psychologists began to put forth the idea that mothers should show their children as little affection as possible. They thought too much affection – coddling or pampering – could make them weak. Babies should not be babied, they said.

Harry Harlow was a psychologist at UW-Madison in the 1950’s who thought differently, and used rhesus monkeys to study social behaviors, social isolation, and maternal dependence. Harlow believed that mothers played a critical role in the development of their children, although his cruel and unethical methods ignited the animal rights movement and put in place standards for usage for animals in scientific experiments.

He created the “pit of despair,” separating baby monkeys from their mothers; left in the pit for up to one year after birth. Harlow wrote, “One of six monkeys isolated for three months refused to eat after release and died five days later… the effects of six months of total social isolation were so devastating and debilitating that we had assumed initially that twelve months of isolation would not produce any additional decrement. This assumption proved to be false; twelve months of isolation almost obliterated the animals socially.”

One of his most famous experiments presented baby monkeys with two mother surrogates; the first was a bare wire surrogate that provided food and the other was a surrogate that didn’t offer food but was covered with a soft cloth. The monkeys stayed with the soft surrogate, leaving it only briefly for food. For primates there is a powerful biological need for connection that can be as powerful as our drive for food.

In 1990, Vincent Felitti presented the first data connecting childhood trauma to adult obesity at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in Atlanta. Dr. Felitti was an internist with an obesity clinic in San Diego, as well as chief of Kaiser-Permanente’s Department of Preventive Medicine, at that time the largest medical screening program in the world. While working with his patients, he discovered that many reported being sexually abused as children, or experienced other significant traumatic events. His findings generated significant negative feedback, as there was no precedent for that kind of causal relationship.

Fortunately, not all the feedback was negative. Dr. Robert Anda was curious about the impact that childhood trauma might have on adult health. An epidemiologist from the CDC, he encouraged Dr. Felitti to begin a much larger study, drawing on a general population. Anda and Felitti became co- investigators of the CDC-Kaiser Permanente Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study, one of the largest studies of childhood abuse and neglect on later health and wellbeing.

The original ACE Study was conducted at Kaiser Permanente from 1995 to 1997 with two waves of data collection. 17,421 Health Maintenance Organization members from Southern California agreed to complete confidential surveys regarding their childhood experiences (from birth to age 18) and current health status and behaviors.

The ACE survey consisted of ten questions that covered carefully defined categories of early childhood trauma, including physical and sexual abuse, physical and emotional neglect, and family dysfunction. Each ‘yes’ answer was scored as one point, leading to a possible ACE score ranging from one to ten.

The study’s disturbing results showed that traumatic life experiences during childhood and adolescence are much more common than previously thought. Around half the sample had experienced at least one adverse situation, and 25 percent had experienced two or more. Adverse childhood experiences occur across all levels of income and education. Substance abuse in the family was most common, followed by sexual abuse and mental illness.

In addition, the study showed that while adverse experiences are usually studied separately, they’re actually interrelated. For example, a person doesn’t usually live in a family where one person is in jail, but everything else is perfect; or the mother is beaten but there are no other problems. Incidents of neglect or abuse are not isolated events. For each additional adverse event the toll in later damage increases exponentially.

Dr. Felitti wrote, “Contrary to conventional belief, time does not heal all wounds, since humans convert traumatic emotional experiences in childhood into organic disease later in life.”

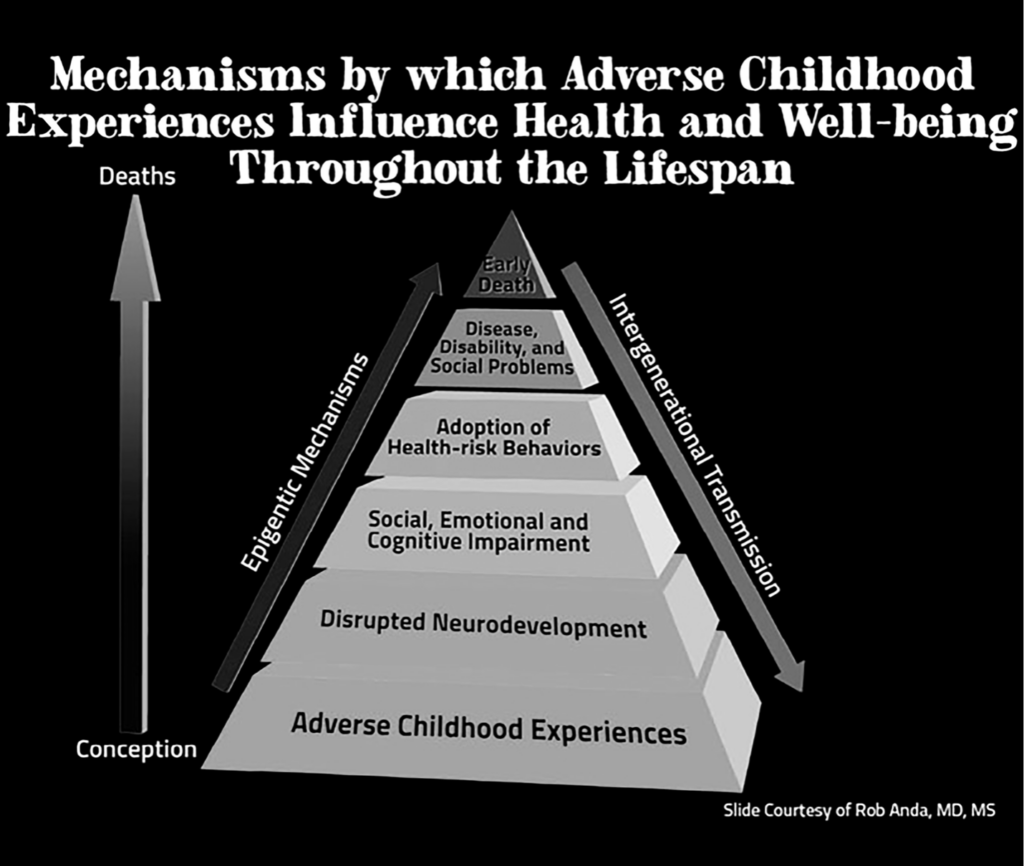

The impact of trauma is pervasive throughout a person’s entire life. Higher ACE scores are correlated with problems at work, financial problems and lower lifelong income. Chronic depression rises dramatically and exponentially, along with self-acknowledged suicide attempts. There is a five thousand percent increased likelihood of suicide attempts from an ACE score of zero to six. An increased ACE score is predictive of smoking, obesity, alcoholism, sexually transmitted diseases, asthma, heart disease, depression, and premature death.

The stress of chronic abuse may result in anxiety and may make victims more vulnerable to problems such as post- traumatic stress disorder, conduct disorder, and learning, attention, and memory difficulties.

The first person to document the long-term effects of harsh conditions in Romanian orphanages was Harvard psychologist and neuroscientist Charles Nelson. In 2000, he and his colleague, Dr. Stacy Drury, established a lab inside an orphanage to study the effects of early childhood neglect on the developing brain. At that time, although the children received adequate food and shelter, they were given very little affection or stimulation.

Their research demonstrated the profound impact of early childhood neglect, through the measurement of shortened telomeres. Telomeres are the caps at the end of each strand of DNA, which protect our chromosomes. Shorter telomeres – connected to premature cellular aging – are a physical measure of biological, rather than chronological, age. The number of traumatic events experienced as a child, directly influences shorter telomere length as an adult. Early adversity lodges itself in the body through biological embedding, which is measured through shorter telomeres.

Fortunately, Nelson’s research team also showed that, while damage from biological embedding can be devastating, it can also be halted or even reversed if children are able to benefit from a more nurturing environment.

A program for homeless children in St. Paul uses CalmConnect multiple times a day. Living in the shelters, most of the children (2-7 years of age) have a high ACE score and a very small nuclear family. They crave the love and attention of other people. We were invited to visit the school one morning and were amazed to see that all of the children had ‘adopted’ different people (from the varied ethnicities on the screen) to be a part of their larger family. One of the biggest surprises was the group’s shared, tacit acknowledgment and recognition of ‘family members.’ There were huge smiles all around as children pointed to people on the screen, calling out, “There’s your grampa! That’s my cousin! Look at your brother! I see your auntie!” We watched as the program buoyed their spirits, helped them to become calm and focused, and allowed them to feel safe and belong to the family they had created for themselves.

We believe that regular and sustained use of CalmConnect supports emotional well-being in the same way that eating healthy foods and exercising supports physical and mental well-being. The safety and affiliation provided by CalmConnect may help to neutralize or in some cases even reverse the effects of adverse experiences; hopefully, minimizing their effects.